The Black Sea

Tanerian - or The Black Sea - the fishermen call the waters North of Babilani. Here they can throw out their lines and never catch anything but drifting lumps of kelp and seaweed. And if they catch a rare fish, it will always have large angular jaws, eyes like glass plates and cartilage instead of bones. Bad luck follows anything you pull out of the Black Sea, the fishermen say.

At night the waters crackle with seafire, and jellyfish clump in large colorful blankets, so one could almost walk dry shod along the ship. Then the dark waters sing of beautiful, hidden worlds in the deep. The fishermen of Babilani fear this song more than anything else. If a ship is caught by Northern winds, the men aboard will not feel safe until they see the blinking of the lighthouse outside Kheretai, the Babilani harbor.

Kheretai - The Port of Babilani

One could well call the large and busy port a city in its own right, with the lighthouse The White Star as its most impressive landmark. Kheretai is so crowded that the longshoremen lower the masts and hoist the ships several stories above sea level before unloading the cargo.

Every visitor to Babilani arrives here, traders from all the seven islands, children from well off island families being sent to boarding schools in the capitol, sailors seeking work, and of course the large number of tourists that arrive every day.

The air is thick with an everlasting smell of dried seaweed, tarred poles and fried shellfish. And all the time seagulls screech, traders bicker with the port police, dockhands sing in time while hoisting cargo.

Babilani - East Stone Town

The part of Babilani lying inside the city walls is called Stone Town by the inhabitants. Inside the city walls are overgrown backyards, crooked alleyways, bridges and waterways. Many of the buildings are built so close that the only access is through one of the many canals. Stone Town is again divided in two, with the west side as the richest, and the east side as the poorest, but proudest.

Hundreds of years ago the stone giants built an elaborate system of ducts and canal locks, waterwheels and fountains. The river flowing from Fog Mountain made Stone Town a vigorous, vibrant part of Babilani. But now the waterways are dry, the pumps are empty and the hanging gardens have all withered.

The people of East Stone Town are a proud lot. They all claim to descend directly from Shamorlah the Star Daughter herself, and no matter what squalor they live in, they look down on anybody not from their neighborhood.

The Bazaars of Babilani

The traders of Babilani have a reputation for being ruthless, and none more so than Lankendem. It is a constant joy for the other traders to watch him unload a broken glockenspiel or some pieces of colored glass on an unsuspecting tourist. He will cry and whimper with pain, drying tears and sweat from his face, loudly complaining that he is being robbed. All the traders of Babilani envy Lankendem his skill at hiding the pleasure resulting from an unfair deal.

The Tower of Babilani

Fourteen hundred years ago Shamorlah the Star Daughter arrived at the island of Babilani with seven ships. The chronicles relate that a fierce dragon lived on the plains where the tower now stands. Her companions were afraid, but Shamorlah asked the dragon three riddles. Unable to answer, the dragon turned to stone. That evening Shamorlah planted the dragon's teeth in the ground. The next morning giants grew from the plains, and these giants started to build the Tower of Babilani.

The Hall of Ten Mirrors

In the library of Babilani they multiply, the Nardaks, the tiny elvish shapes that flutter like birds under the tie beams of the tower. They take little notice of humans, or Clumsies, as they call them. The Nardak social order is built on numbers. They are ruled by The Council of Ten, who gather in the Hall of Ten Mirrors whenever important issues are to be decided.

Nardaks are nimble and surefooted, always dancing or running, always the sound of glass shoes, tap-tap, under the rooftops. Nardaks may live to be many hundreds of years old. It is even rumored that they never really die, they just solidify, their skin hardening to smooth porcelain, their eyes sinking, their faces becoming painted masks.

Where the Stone Giants are masters of large scale construction, the Nardaks are masters of Intricatery, which is their name for the clockworks, locks and glockenspiels they take so much delight in.

The Desert Garden

Once a flood rolled dark and heavy with snow melt from the crags of Djonerai. North of the capitol corn fields and wheat fields stretched as far as the eye could see. But after the river ran dry, people named this area Wadi Natrun, the Salt Fields. Most of the farms are abandoned, and every year the desert eats a little more of the few remaining acres.

Some wanderers who get lost in the desert speak of The Desert Garden. They say that soft rain cools their brows, that the air smells of dewy flowers, that brooks sing among the boulders. All the time they sense something in the corner of their eyes, a remnant of rugs and oil lamps, an echo of the woman who once lived in the garden.

But when morning comes the lost wanderers all wake up with dust in their mouths. And once again they will only see sand, gravel and tufts of brown desert grass.

The Cave of Winds

By the foot of the Fog Mountains miners have burrowed for hundreds of years in search of Pelukra, the sun crystals that light up Babilani homes. These crystals are able to absorb sunlight during the daytime and will shine for several hours after dark.

Following the river further into the Fog Mountains, one will find a small valley where the river has dug deep caves out of the jagged hillside. It is told that a madman lives here, in the Cave of Winds, and that he lives forever. When the wind blows down the valley, and the melting of the snowcaps washes through the caves, an eerie howling can be heard for miles around. Some say its just the wind reverberating, others say its the screaming of the madman.

Djonerai - Mountain of the Stone Giants

High in the mountains north of Babilani lives a tribe of giants with their own customs and their own creed. It is said that they were here even before Shamorlah the Star Daughter arrived with seven ships from the East. They are twice as tall as ordinary men, and three times as wide, with thighs and upper arms like logs of lumber.

Stone Giants they are called, not that they are made of stone, but because they are the most skillful builders in all the seven islands. Djonerai they call their homeland. On top of the highest peak they have erected an enormous sundial. Below the peak lies The Field of Sleeping Giants, the ancient burial ground of Djonerai.

The Stone Giants were the ones who built the Tower of Babilani, the old city walls and the catacombs underneath the inner city. Once they were in high demand as builders, and even as longshoremen down in the harbor, but lately not many Stone Giants have left the mother mountain.

Alkamar - The Village in the Moonlight

Most of the Babilani coast is marshland, thick with thorny bushes, seeping with bracken water. But far north in Babilani lies the village Alkamar, where men and women have harvested the sea for a thousand years. Standing on a hilltop and looking down, one sees the village resting in the bottom of a crescent-shaped fjord. It is said that whatever comes from the sea, first arrives at Alkamar.

The Dragonfield

There are four gates in the heavy walls circling the city of Babilani. Outside the Southern Gate longshoremen groan under cargo from all the Seven Islands. To the west traders and merchants erect their canvas stalls and haggle with customers in an everlasting din. Outside the Northern Gate salt fields and desert stretches all the way to the Fog Mountains.

And outside the Eastern Gate lies the Dragonfield, where Norka the dragon slumbers. It is said that the person who can solve the Dragon's Riddle is the rightful heir to the throne of Babilani.

The Catacombs

Over the rooftops and hanging gardens looms the Tower of Babilani. Seven levels above the ground, shaped like a spiral, the dried clay burning white in the sunlight. Here the scriveners have collected all the knowledge of the island kingdom since the dawn of time, when Shamorlah the Star Daughter arrived in Babilani.

In the floor of the hall inside the towers are five heavy iron doors, leading down to the seven levels underneath the tower. When the river flowed through Babilani it was possible to open these doors. But the river is dry now, the canals filled with mud and sand, the cracked waterwheels cobwebbed and dusty.

One day the river will flow again. One day the underground machinery will hum with energy from cascading waters, and then it will be possible to reach the catacombs underneath the tower.

In English

Alternativer

- Til forsiden

- Flash spill og aktiviteter

- Om prosjektet

- Fraktale gallerier

- Om øyriket Babilani

- Fortellinger

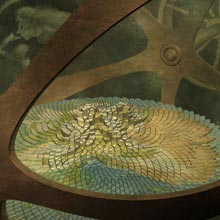

Panielo, the world model.

Panielo, the world model.